Dates de projection de Film Covid: Totalitarisme helvétique?!

JEUDI 7 Mars 21h – LAUSANNE

Zinema – Rue Maupas 4 – 1004 Lausanne

Ensuite programmation régulière.

SAMDEI 9 Mars 20h – ORON-LA-VILLE

En présence du Réalisateur

Cinéma d’Oron – Le Bourg 13 – 1610 Oron-la-Ville

Ensuite programmation régulière.

Cinéma d’Oron (cinemadoron.ch)

JEUDI 14 Mars 19h – NEUCHÂTEL

Avant-Première neuchâteloise en présence de Chloé Frammery et du Réalisateur

Cinéma Minimum – Quai Philippe-Godet 20 – 2000 Neuchâtel

Ensuite programmation régulière.

MARDI 19 Mars – OESINGEN

Avant-Première en suisse alémanique en présence du Réalisateur

Kino Onik – Hauptstrasse 67 – 4702 Oensingen

Ensuite programmation régulière

Reservation – Kino Onik (cineapp.ch)

VENDREDI 5 Avril 20h – SAINTE-CROIX

En présence du Réalisateur

Cinéma Royal – Avenue de la Gare 2 – 1450 Sainte-Croix

Ensuite programmation régulière.

Dimanche 21 avril SOLEURE, Kino Uferbau

En présence du réalisateur

Ensuite programmation régulière

JEUDI 25 Avril 20h30 – VEVEY

En présence de Chloé Frammery et du Réalisateur. Jean-Dominique Michel sera également présent pour signer son livre.

Cinéma Rex I – Rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau 6 – 1800 Vevey

EN PRÉSENCE – TOTALITARISME HELVÉTIQUE | Cinérive (cinerive.com)

Date à venir – FRIBOURG

Avant-Première fribourgeoise en présence de Chloé Frammery et du Réalisateur

Cinéma Corso – Boulevard de Pérolles 15 – 1700 Fribourg

Ensuite programmation régulière.

Film covid (Totalitarisme helvétique?!) (2023)

Bande-annonce en français

Trailer auf Deutsch (en allemand)

Les conséquences du Covid sur la mortalité sont claires quelque 8 000 morts en 2020. Les statistiques de l’OFSP sont indiscutables.

L’épidémie n’a pas eu d’incidence sur la mortalité des travailleurs, et encore moins chez les jeunes. Les personnes affectées mortellement étaient, dans leur très grande majorité, très âgées et très malades.

Les quelques mois d’espérance de vie perdus par la population en 2020 ont été récupérés en 2021, année de sous mortalité, année du pass !

Mais qu’en est-il de la répression liée au nonrespect des mesures répressives du Conseil fédéral, décrétées dans l’urgence ? Un tabou. Les historiens répondront, peut-être, à cette question avec en mémoire la condamnation du gouvernement suisse par la Cour européenne des droits de l’homme le 15 mars 2022, pour ses restrictions aux libertés politiques et syndicales.

Ce film dresse un panorama sur ce sujet gênant.

Dossier de présentation

Affiche

Galerie photos

Entretien sur Radio Libre

Présentation du film par Daniel Kunzi (Avant-Première)

Pomme de discorde – alerte pesticide (2021)

Suisse | 2021 | Société Productions Maison | Production Daniel Künzi | Montage

Dejan Savic | 70 min.

Après avoir accompli la moitié du tour du monde des milliers de tonnes de pommes chiliennes sont mangées en Suisse. Elles sont cultivées par des temporaires qui se définissent comme les esclaves du XXIème siècle, arrosées aux pesticides produits notamment en Helvétie, mais interdits dans notre pays. Les enfants sont les principales victimes de ces toxiques.

IMAGES

PROJECTIONS

Journées cinématographiques de Soleure | Coopérative Polygone-Esplanade des récréations – Meyrin | Acquarossa – Bellinzona | cinéma Bellevaux – Lausanne | Film für die Erde – Suisse allemande | Festival du film Vert 2021 – Charmey, Lausanne, Colombier, Rue, Plan-les-Ouates, Echallens, Genève | Zinéma – Lausanne | Scala – La Chaux-de-Fonds | Cinémont – Delémont | Oron | Saint-Imier | Breuleux | Noirmont | Porrentruy | Neuchâtel | Berne

FESTIVALS

- Solothurn, 56. Solothurner Filmtage

20.01.2021 – 27.01.2021

LIENS

https://swissfilms.ch/fr/movie/pomme-de-discorde-alerte-pesticide/52FD84E9BB2E4FA2BEFB5A912890CDC0

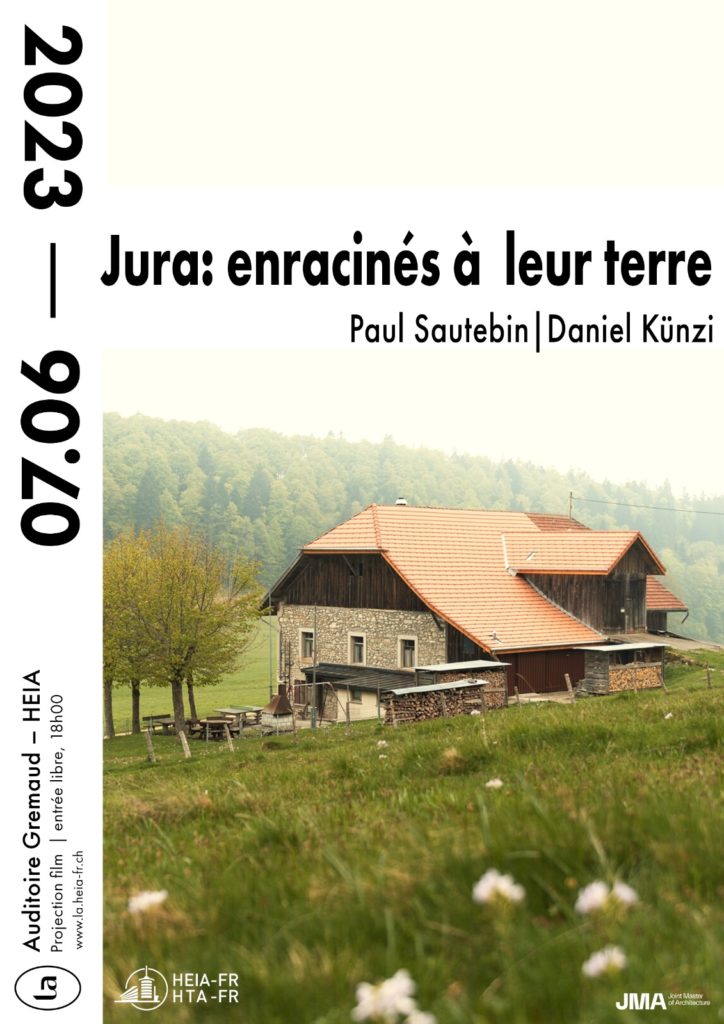

Jura: enracinés à leur terre (2017)

Réalisateur-trice : Daniel Künzi | Montage : Dejan Savic | Musique : Corinne Galland | Pays : Suisse | Année : 2017 | Durée : 78 min | Langue(s) : Français | Sous-titres : Allemand

Pendant une année, j’ai suivi trois fermes jurassiennes bio dans les Franches montagnes. L’existence de ces paysans est précaire. La libéralisation des prix en Europe vient bouleverser leur existence. A cela s’ajoute la sécheresse, les maladies et les accidents. Et pourtant ils exercent leur métier de paysan avec passion.

Leurs fermes seront-elles encore occupées par des paysans dans vingt ans ?

Disponible en DVD pour 25 CHF TTC (commande) Pochette DVD [PDF] Affiche A2 [PDF]

L’agriculture suisse ne peut nourrir que la moitié de sa population, paradoxalement, plus il y a d’habitants, moins il y a de terres cultivables sacrifiées aux routes, à l’urbanisation, etc. Chaque jour deux à trois exploitations agricoles disparaissent. La diminution des terres cultivables signifie non seulement que la souveraineté alimentaire du pays diminue, mais qu’il est toujours plus difficile d nourrir les animaux d’élevage. Chaque année près de 320’000 tonnes de céréales sont importées essentiellement d’Amérique, pour nourrir des cochons, des poules, et des vaches afin notamment de produire du fromage pour l’exportation! Et ceci sur fond de surproduction périodique. Sur le plateau suisse, la production agricole est dominée par l’agriculture industrielle, les sols sont devenus moins productifs et le recours aux engrais et aux pesticides, généralement des dérivés du pétrole, est devenu la règle. Comme le dit Paul Sautebin, un paysan du Jura : « Nous n’allons pas dans le mur, nous sommes dans le mur»!

Face à cette situation, des paysans de montagne du Jura ont adopté une manière différente de produire et de consommer, nous les avons suivis une année, ils survivent aujourd’hui avec l’aide des payements directs qui représentent plus de 80% de leur revenu. Ils ont opté pour une agriculture bio: pas de pesticide, ou d’engrais chimiques. Leurs conditions de vie sont rudes : lever à 5 heures du matin pour la traite, 365 jours sur 365, nombreux accidents et autres maladies professionnelles. Et leur avenir est sombre, marqué par la concurrence internationale, la baisse constante des prix, ainsi que les votes du parlement fédéral

PROJECTIONS

- Porrentruy – novembre 2019

- Delémont Cinéma Lido en présence des intervenants du film – décembre 2018

- Meyrin – mars 2018

- Genève Metro Kino Boulot – mars 2018

- Meyrin et Echallens – mars 2018 Festival du Film Vert

- Solothurn Kino Canva Klub – novembre 2017

- RTS – novembre 2017

- Zürich Kino Houdini – octobre 2017

- Bulle Prado – octobre 2017

- Fribourg – septembre 2017

Cinéforom – Plainte contre l’Etat de Genève au Tribunal fédéral (2017)

Tribunal fédéral.

Ainsi donc le Tribunal fédéral a jugé mon recours contre l’Etat de Genève qui octroie quelques millions à Cinéforom, cette institution cinématographique ne garantit pas formellement un accès au juge en cas de refus d’une subvention. Nous contestions une loi datant de 2013 visant un financement triennal.

D’entrée de jeux un juge romand, observe que le TF ne doit pas entrer en matière puisque la loi a pris fin le 31 décembre à minuit en l’an 2016. Et que la longueur de notre argumentation est trop longue et responsable des trois ans écoulés entre notre recours et son jugement !? Il ajoute qu’il est par exemple illisible « écrit en petit caractère » ! On aurait pu espérer que ce juge, payé au bas mot un quart de million par année, s’achète des lunettes. Donc refus de discuter du fond de la question. Un juge suisse alémanique lui fait remarquer que le texte est peut-être difficile à lire, mais que le problème est évident. Une entité publique ne peut pas donner des millions à une fondation privée sans qu’elle ne garantisse des voies de droit en cas de refus d’une subvention.

Après 90 minutes de palabres et une interruption, l’entrée en matière est enfin acceptée.

On entendra ce curieux argument, toujours de la bouche d’une romande : où allons-nous si nous donnons des voies légales de recours à tous les bénéficiaires de subventions privées. Citant au passage les statuts de Cinéforom dont le financement est public, mais peut aussi récolter des dons. Ce juge n’a pas remarqué que Cinéforom n’avait jamais reçu de dons privés. Du reste en deux click elle aurait pu le vérifier, mais le tribunal est précisément situé à la rue Mon Repos et pas Mon Travail. On a aussi entendu : « On ne va pas changer la jurisprudence du TF pour le cinéma » !?

Je lis dans la presse du jour qu’en France les réalisatrices ne reçoivent que le 42% du salaire de leurs homologues masculins, à Cinéforom elles ne reçoivent que la moitié moins (Rapport d’activité 2016). Quel progrès. Si elles veulent contester cette discrimination auprès des tribunaux, je leur souhaite bonne chance, car la voie juridique indiquée par le président du TF pour faire valoir leurs droits est digne d’un chemin de croix, et dans un labyrinthe ! C’est par trois voix contre deux, après plus de trois heures de délibérations que le TF a rejeté notre plainte, il s’en est fallu d’un cheveu !

C’était la guerre – les légionnaires suisses (2012)

Durée 65 minutes | 2012 | Scénario Gilles Perrault | Réalisation Daniel

Künzi | Conseiller historique Peter HUBER | Traduction Mary Honderich

Les Suisses sont plus connus pour leurs «humanitaires » que leurs militaires. Plus de 3 000 Suisses se sont engagés dans la Légion étrangère française au cours des guerres d’Indochine et d’Algérie. Issus de milieux défavorisés, ils fuyaient la misère, leur pays ne leur offrait aucun avenir. Ils étaient le fer de lance de l’armée coloniale française. Aujourd’hui, ils parlent de leur vie de légionnaire, de leurs formateurs (souvent d’anciens SS). Ils décrivent ce qu’est la guerre avec son cortège de massacres, d’exécutions sommaires et de tortures.

Ces Suisses préfigurent les mercenaires employés aux quatre coins du globe dans des armées privées : Irak, Libye, etc.

Un film historique qui évoque le futur !

MÉDIAS

La Légion autrefois bercail pour des Suisses démunis – Swissinfo

PAROLE AU PUBLIC (senscritique.com)

Pourquoi pas les Suisses après tout

Mon avis—

Un très bon reportage sur une des innombrables facettes de la légion. Un document intéressant à découvrir, juste pour son opinion personnelle. Ma note sera de : 8/10

L’histoire sans fard de la légion étrangère vue par des Suisses. Loin des clichés sur l’esprit chevaleresque, et de toutes les légendes véhiculées au cinéma. Ces Suisses racontent leur vie de mercenaires sans foi ni loi : leurs crimes, les tortures, les viols, etc.

Un film qui en dit beaucoup, et peut-être trop (!) sur la « culture d’entreprise » de la légion, toujours le fer de lance des opérations néo-coloniales françaises, comme aujourd’hui au Mali.

C’était la guerre : Les légionnaires suisses par Sparfell

Ce documentaire du suisse Daniel Kunzi est constitué d’interviews d’anciens légionnaires suisses, d’interviews de membres du viêt minh et de maquisard algériens et d’images d’archive. Le montage respecte la chronologie des événements : de l’enfance difficile de ces futurs légionnaires à leur participations aux dernières guerres coloniales de la France : l’Indochine et l’Algérie. Ces individus nous racontent ainsi la guerre telle qu’ils l’ont vécus avec son lot de massacres, de tortures et d’exécutions sommaires.

Ici pas de gloire, pas de fard, pas de clichés. Juste les regrets ou les bons souvenirs de ces hommes désormais âgés qui portent un regard plus ou moins fier et sincère sur leur passé. C’était la guerre.

Le film démarre sur la question suivante : pourquoi des jeunes hommes issus d’un pays pourtant épargné par la seconde guerre mondiale s’engagent en nombre dans la légion au sortir de la guerre ? Cependant, D.Künzi dépasse largement sa problématique initiale pour dresser le tableau des guerre coloniales française de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle peint par les combattants ayant pris part à ces conflits dans un camp comme dans l’autre.

Il s’agit donc d’une multitude de témoignages subjectifs ayant pour objectif de restituer un fragment de ce que furent ces événements appartenant désormais à l’histoire.

Il n’est pas question de sensationnel, le réalisateur s’étant contenté de retrouver et d’interroger (parfois avec difficulté) les différents protagonistes afin qu’ils délivrent leur témoignage.

Le film est sorti en Suisse en octobre 2013, je ne sais pas quand est prévue sa sortie française (si elle est prévue).

DIFFUSIONS / PROJECTIONS

TV5 Monde

Cyberterrorisme, réalité et fiction (2011) – Conférence

Intervention à la Conférence de l’Académie de la radio et de la TV (Moscou) à Chypre en 2011 – Original en anglais en fin d’article

Cyberterrorisme, réalité et fiction

D’une part, les militaires disent qu’il ne faut pas confondre le son d’un tambour avec celui d’un canon, d’autre part, ceux qui ont lu Clausewitz n’oublieront pas sa remarque : les stratégies sont toujours en retard d’une guerre.

Tout au long de mon travail cinématographique, je me suis penché sur la Première Guerre mondiale, la guerre civile espagnole, la Seconde Guerre mondiale, la guerre d’Indochine, puis celle d’Algérie, etc. En réalisant des interviews avec des témoins de ces périodes, j’ai pu me faire une idée précise de ce que l’on appelle la » terreur « . Voici un exemple tiré de mon prochain film qui traite des mercenaires suisses de la Légion étrangère française, engagés pour faire le » sale boulot « .

Extrait : Témoignage de Schupbach

1) C’est nous qui avons fait le massacre avec le FLN. Ils ont eu énormément de morts. Nous avons aussi fait un massacre.

Extrait : Témoignage de Werner Beutler :

2) On les entendait. « La Légion, sortons d’ici. » Ils savaient que nous étions durs. Nous faisions rarement des prisonniers. Certains ont levé les bras : « Vive de Gaulle, vive la France ». « Nous avons appuyé sur la gâchette. C’était fini.

Extrait : Témoignage de Schupbach

3) Il était très rare qu’un Arabe parle. On pouvait les torturer comme on voulait. Par exemple, pour la torture du bain, il y avait un grand type. Ils lui plongeaient la tête dans l’eau et comptaient un…deux-trois…quatre…cinq, puis ils lui sortaient la tête de l’eau. La fois suivante, ils ont compté jusqu’à dix. La fois suivante, ils comptaient jusqu’à 30 secondes, puis jusqu’à une minute. Pour moi, c’était du pur sadisme.

La terreur était partout en Algérie. Au cours de ce conflit, entre 1954 et 1962, un quart de million d’Algériens ont perdu la vie alors que les Français en ont perdu dix fois moins. Ces témoignages nous permettent de comprendre ce qu’est la terreur, au même titre que le tableau Guernica de Pablo Picasso ou la musique d’Arnold Schoenberg. Un survivant de Varsovie. Il est important de ne pas confondre la peur et la terreur.

Nous sommes proches de la Grèce, une civilisation qui a donné naissance et nourri notre philosophie. Je pense qu’il serait utile de revenir à Platon et au célèbre dialogue entre Socrate et Ménon. Cela peut nous aider à ne pas nous égarer lorsque nous parlons de cyberterrorisme. Car le problème est de bien comprendre le sens de ce mot.

Dans son dialogue avec Ménon, Socrate pose une question essentielle : comment faire de la recherche sur un objet quand on ne sait pas ce que c’est ? C’est ce qu’on appelle le paradoxe de Ménon et la conclusion finale de ce paradoxe est la suivante : comment pouvons-nous savoir quand notre recherche est terminée alors qu’au départ nous ne savons pas ce que nous cherchons exactement ?

Si ma compréhension du sens du mot » cyber » et du sens du mot » terrorisme » est correcte, alors je dois admettre que leur connexion me crée de nombreuses difficultés. Au cours des dix dernières années, le mot » terrorisme » a été adapté à tout type de situation. Au point qu’un leader palestinien immanent, Yasser Arafat, qualifié dans le passé de terroriste par les Etats-Unis et par Israël, reçoit le Prix Nobel de la Paix. Au même titre que Menahem Begin, qui a organisé l’attaque terroriste contre l’hôtel King David en Palestine.

J’ai essayé de trouver une définition convaincante du cyberterrorisme, mais je ne l’ai pas encore trouvée. Vous pourrez certainement m’aider. Par exemple, on entend souvent parler d’attaques sur Internet. Mais à mon avis, il s’agit d’une malveillance, d’une variante de la guerre de l’information, de » l’intox » qui apparaît lors de toute guerre. Mais nous sommes très loin des conséquences dévastatrices du bombardement par l’OTAN de la télévision libyenne ou du bombardement de la télévision serbe. J’ai visité son bâtiment à Belgrade il y a quelques années. Il était encore détruit, un monument à la mémoire des 16 victimes du bombardement.

Poursuivant mes recherches, j’ai essayé de savoir s’il y avait déjà eu des cyberattaques terroristes qui avaient fait autant de victimes que dans les témoignages cités plus haut. Je n’ai pas cherché à savoir s’il y avait eu des cas de torture, de massacre, etc. Je n’en ai trouvé aucune. Cela n’exclut pas que demain un groupe de terroristes, avec l’aide d’un » hacker » puisse prendre le contrôle d’un réacteur nucléaire ou disons de missiles nucléaires afin de les diriger vers des villes qui ont été ciblées.

Dans ce cas, il existe des moyens de prévenir une telle attaque. Les moyens existent et ils sont là. En fait, l’illégalité de la bombe nucléaire ne fait aucun doute. La Convention de La Haye de 1907 (articles 25 et 27, complétés par l’article 24 de la Convention de 1923) interdit les bombardements aveugles de populations civiles. Il existe de nombreuses autres résolutions du même type, comme le caractère criminel de l’utilisation de la bombe nucléaire (résolution 1653 XVI de l’ONU du 24 novembre 1961).

La conclusion est évidente. Ce ne sont pas quelques cyber-terroristes potentiels qui posent problème. Le vrai problème vient d’un monde qui s’est développé au mépris de l’humanité et du respect des normes juridiques internationales, des moyens qui permettent d’imaginer la terreur à une échelle apocalyptique.

Daniel Künzi

Genève/Chypre octobre 2011

TEXTE ORIGINAL EN ANGLAIS

Cyber terrorism, reality and fiction

On one hand, the military says that one must not mistake the sound of a drum for that of a canon, on the other hand, those who have read Clausewitz won’t forget his remark: strategies are always one behind on a war.

Throughout my film work, I have looked into the First World War, the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, the war in Indochina, then the one in Algeria, etc. Having directed interviews with eyewitnesses of these periods, I have been able to develop my own precise idea about the thing that is called « terror ». Here is an example taken from my next film that deals with Swiss mercenaries fighting in the French Foreign Legion, hired to do the « dirty work »

Extract: Schupbach’s testimony

1) We were the ones that did the massacre with the FLN. They had an enormous number of dead. We had a massacre as well.

Extract: Werner Beutler’s testimony:

2) We could hear them. “The Legion, let’s get out of here.“ They knew we were hard. We rarely took any prisoners. Some of them lifted up their arms “Vive de Gaulle, vive la France. “ We pulled the trigger. That was the end of it.

Extract: Schupbach’s testimony

3) It was very rare for an Arab to talk. You could torture them any way you wanted. For example the bath torture there was a big guy. They dunked his head in the water and counted one…twothree..four..five and then they lifted his head out of the water. The next time they counted until ten. The time after it was 30 seconds, then one minute. For me this was pure sadism.

Terror was everywhere in Algeria. During this conflict between 1954 and 1962, a quarter of a million Algerian lost their lives while the French lost ten times less. These eyewitness testimonies allow us to understand what terror is, in the same way as Pablo Picasso’ painting Guernica or Arnold Schoenberg’s music. A survivor from Warsaw. It is important not to confuse fear with terror.

We are close to Greece, a civilization that gave birth and nourished our philosophy. I think it would be useful to return to Plato and to the famous dialogue between Socrates and Meno. This can help us from getting lost when we speak about cyber terrorism. For the problem is to truly understand the meaning of this word.

In his dialogue with Meno, Socrates asks an essential question : how can we do research on an object when we don’t know what it is ? This is what is called Meno’s paradox and the final conclusion of this paradox is this: how can we know when our research is over when at the beginning we don’t know what exactly we are looking for?

If my understanding of the meaning of the word « cyber » as well as the meaning of the word « terrorism » is correct, then I must admit that their connection creates many difficulties for me. In the last ten years, the word « terrorism » has been adapted to any type of situation. To the point that an immanent Palestinian leader, Yasser Arafat, qualified in the past as a terrorist by the United States and by Israel, receives the Nobel Peace Prize. In the same way as Menahem Begin, who organized the terrorist attack on the King David Hotel in Palestine.

I have tried to find a convincing definition of cyber terrorism, but I have yet to find one. Certainly you will be able to help me out. For example, one often hears about attacks on Internet. But in my opinion, this is a case of malicious intent, a variant of the war on information, « intox » that appears during any war. But we are very far away from the devastating consequences of NATO’s bombing of Libyan television or the bombing of Serbian TV. I visited it’s building in Belgrade a few years ago. It was still destroyed, a monument to the 16 victims of the bombing.

Continuing my research, I tried to learn if there had previously been cyber terrorist attacks that had made as many victims as seen in the testimonies quoted above. : torture, massacre, etc. I found none. That does not exclude the possibility that tomorrow a group of terrorists, with the help of a « hacker » could take control of a nuclear reactor or say nuclear missiles in order to direct them towards cities that have been targeted.

In such a case, there is ways to prevent such an attack. The means exist and they are right there. In fact there is no doubt about the illegality of the nuclear bomb. The 1907 Hague Convention (articles 25 and 27, completed by article 24 of the 1923 Convention) forbids indiscriminate bombings of civilian populations. There are many other resolutions of the same kind, such as the criminal nature of the use of the nuclear bomb (the UN resolution 1653 XVI of Nov.24th 1961).

The conclusion is obvious. It is not a few potential cyber terrorists who are the problem. The real problem stems from a world that has been developed with total disregard for humanity as well as the respect for international legal norms, means that allow terror to be imagined on an apocalyptic scale.

Daniel Künzi

Geneva/Cyprus october 2011

Bach rencontre Buxtehude (2010)

avec Marthe Keller et Francesco Tristano Schlimé et Julie Nicolet.

Réalisation Daniel Künzi – 61 minutes-co.

D’abord, il y a la musique. Celle de Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707), considéré à son époque comme le plus grand musicien allemand. Musique jouée au piano (instrument que Buxtehude n’aura jamais connu) par un extraordinaire interprète luxembourgeois, Francesco Tristano Schlimé, né en 1981. Ce que donne à voir « Bach rencontre Buxtehude », c’est principalement cela : un jeune pianiste d’aujourd’hui qui nous interprète Buxtehude. Cela dure une heure et trois minutes. Cela nous habite et nous emporte. Cela nous transporte. Magie.\n\n \n\nEn 1705, Jean-Sébastien Bach, qui a déjà perdu son père et sa mère, a vingt ans. Il a déjà vécu à Eisenach (sa ville natale), Ohrdruf et Lüneburg, il travaille depuis deux ans comme organiste à l’église Saint-Boniface d’Arnstadt, près de Weimar. A l’automne de cette année-là, il décide de parcourir 400 kilomètres à pied pour se rendre à Lübeck, près de la mer Baltique, où réside Buxtehude. Ce voyage, ce séjour, nous sont connus par les Mémoires d’Anna Margareta, la fille de Buxtehude, qui voit débarquer chez elle, un beau jour, ce solide marcheur « plus affamé de musique que de pain ». Les trois mois que Bach passera auprès du maître influenceront autant le vieux musicien, pour les deux années qui lui resteront à vivre, que le futur Cantor de Leipzig. Au point qu’à son retour (également à pied !) à Arnstadt, Jean-Sébastien se fera sonner les cloches par ses paroissiens, qui ne reconnaissent plus sa manière de jouer.

Comme le disait Godard à propos des fondateurs du cinéma : ils auraient pu s’appeler « Abat-jour », ils se nommaient Lumière. Le plus grand génie de la musique aurait pu être baptisé Stein (pierre), il se dénommait Bach (ruisseau ).

Le musicien dont il est question ici, Francesco Tristano Schlimé, est né en 1991. Il aurait pu avoir un nom de famille plus approprié ( Schlim se traduit par «pire» en français). Pour son premier disque chez Universal, il a préféré y renoncer. Pourtant c’est sous ce nom là qu’il a publié plus de vingt CD, autant en classique – de Frescobaldi à Nono – qu’en Electro. Car Francesco Tristano s’est fait aussi un nom dans les discothèques d’Ibiza et d’ailleurs !

Avec ce disque, vous écouterez un piano, comme vous ne l’avez jamais entendu «sonner». Etait-ce bien nécessaire pour la musique de Bach ? A vous de juger ! Le ton est donné dès le prélude de la première Partita de Jean Sébastien Bach. Ce n’est pas toujours «charmant», mais c’est toujours intéressant. Jamais les lignes mélodiques ne se sont développées avec une telle clarté. Une Partita réinventée, l’une des rares œuvres éditées par le maître de l’Art de la fugue. Les basses sont «charnues», précises sans être lourdes, les aigus lumineux ! Un enregistrement aux antipodes des prises de son habituelles de la Deutsche Gramophone Gesellschaft. Pour appuyer sa rhétorique, Francesco Tristano joue des trilles liquides, fluides : un poète qui cherche à nous dire quelque chose. La Gigue qui conclut l’uvre vous électrisera !

John Cage ( 1912-1992 ), s’est notamment illustré pour ses recherches sur les sonorités. Francesco Tristano et son producteur Moritz von Ostwald ont prolongé les expériences de ce compositeur d’avant-garde, en travaillant les sons du piano lors de la post-production. C’est ainsi que la tranquille composition minimaliste In a landscape se métamorphose au gré des interventions des ingénieurs du son. Le timbre du piano se mue progressivement en cloches mystérieuses. Le chant musical s’ouvre aux champs des possibles. \n\nUn parcours musical, une aventure à partager, et un gag à savourer à la fin de l’album, un Menuet de Bach que n’aurait pas renié Walter Carlos, l’arrangeur de la musique du film Orange mécanique.

Daniel Kunzi

Bach-Cage, Francesco Tristano, Universal music 2011

CONCERT ARTE

http://liveweb.arte.tv/fr/video/Versus_2_0___Carl_Craig__Francesco_Tristano___Moritz_Von_Oswald/

C’était mon rêve (2008)

Un documentaire retraçant l’odyssée exceptionnelle des pilotes républicains engagés dans la Guerre d’Espagne (1936-1939). Septante ans après la Guerre d’Espagne, les pilotes russes, ainsi que leurs traductrices, et leurs filles acceptent de relater leurs combats.

Le film C »était mon rêve, 66 minutes 2008, l »histoire des pilotes russes de la guerre d »Espagne et particulièrement du suisse Ernst Schacht a été sélectionné au Festival du film européen de Séville. Ce film a été rejeté par toutes les commissions sélectives, mais pourtant, primé au Festival de Moscou, en compétition aux festivals de Madrid, sélectionné à Granada, Glasgow, Solothurn.